This week we are releasing part 2 of our folk medicine episode. Part 2 features interviews from Flora Youngblood, Ronda Reno, Kenny Runion, and Patricia Kyritsi Howell. Hosts Kami Ahrens and TJ Smith delved deeper into folk medicine and the rich traditions of Southern Appalachia by focusing on plant uses and how medicine has changed over time.

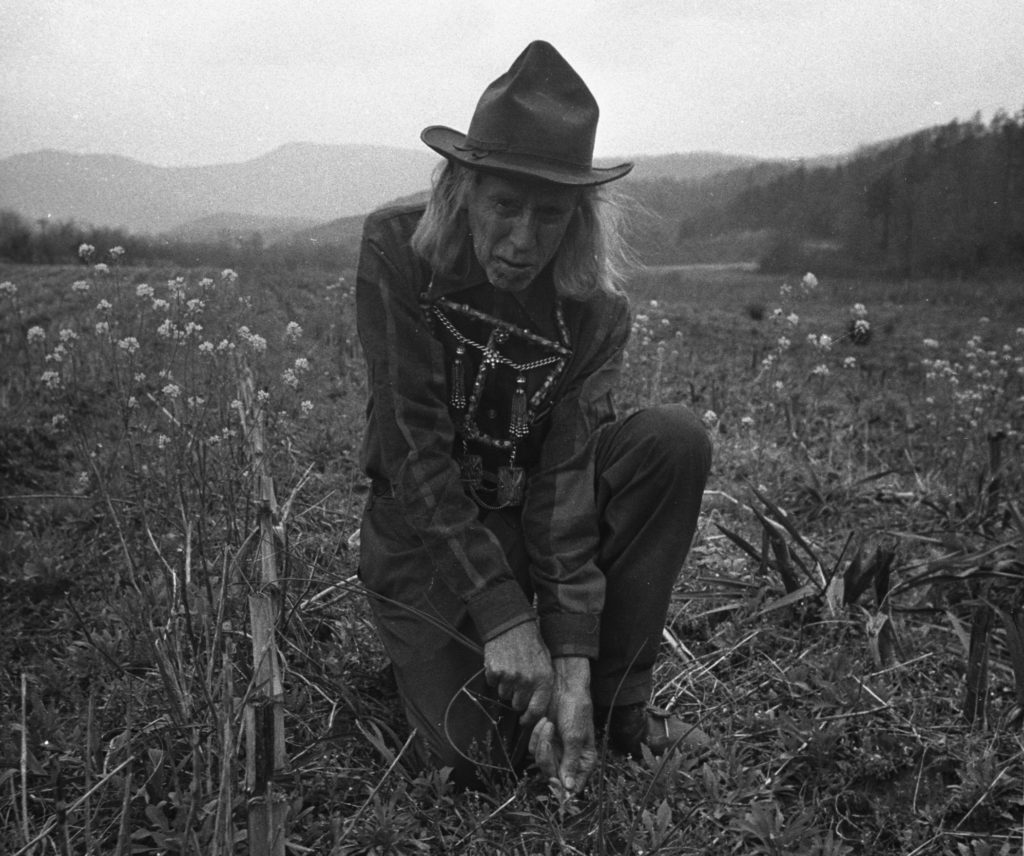

Kenny Runion foraging in a field.

Want to learn more about folk medicine in Southern Appalachia? Check out one of these resources!

The Foxfire Book, edited by Foxfire students

Southern Folk Medicine by Phyllis D. Light

Medicinal Plants of the Southern Appalachians by Patricia Kyritsi Howell

Folk Medicine in Southern Appalachia by Anthony Cavender

www.unitedplantsavers.org

wildhealingherbs.com

Transcripts:

Flora Youngblood (Buford, GA)

Foxfire: And that is where you hunted herbs? Up in the mountains?

FY: Yeah we’d go back up in there and dig ‘em up. My daddy, I’d go with him, and we’d go in there and he’d say “Alright, get that mayapple right there’s some mayapple. Now get this.” I’d hop off and dig it up for him.

FF: You’d dig it, and that’s with a shovel?

FY: Yeah with a little shovel or a little ol’ maddock. Whichever one he’d have in his hand.

FF: Did they have to be a certain quality or anything?

FY: No, just whatever.

FF: And you’d gather the whole plant?

FY: Gather the whole plant

FF: Roots and leaves and all?

FY: Uhuh. He’d take the leaves and make different things out of ‘em and then the roots he’d make other stuff.

FF: Like what?

FY: Now, he’d take the roots and make for sores, for poultices, take it and beat it up.

FF: While they were fresh?

FY: Uh-huh, and then mix it with flour t’where it’d stick together and make little poultices. Instead of beatin’ them up with a cloth, I’d grind ‘em.

FF: Okay, so let’s get the whole process here. You’d go dig the herbs. And then bring back. And then what would you do with them?

FY: We’d wash ‘em real clean. Wouldn’t be a bit of grit on them no where. And then we would trim ‘em and fix ‘em up and dry ‘em. And then powder ‘em.

FF: What did you trim off of ‘em? What would you trim?

FY: A lot of, just the excess, you know looked like one of these vines here with some dead on it you know. And we’d trim off what wasn’t good, what wasn’t good and alive. Some have little dead leaves, you know. We’d trim all that off. Trim it all up and then we would put it in the pan and dry it and powder it up. Put it in little bottles.

FF: How long would it take to dry it and all that?

FY: It wouldn’t take long. You put it in little pans and put in the stove. It didn’t take it long. We had to dry it slow, say about an hour. ‘Cause we had wood stoves and it would take about an hour to dry. And then powder it up. He’d put it in these little bottles. Then when people come, then, he’d hand them a little spoon, he’d know how much to give, for he’d know the case, you know.

FF: The what? The case?

FY: Yeah, he’d diagnose what they had, you know. They’d come to him, they wouldn’t know what was the matter with them. He’d tell ‘em what it was. Then, he would get the herb that went with the disease and dose it out to them.

Ronda Reno (Royston, GA)

RR: Well, I owe everything that I am to my Granny. My great-granny actually. Her name was Vera MacPherson Forrester. And the first thing she ever taught me how to make was rose petal cream. She had some big old pretty red English Cabbage roses. And her and my two great-great aunts—her sisters—Rose and Pearl, they loved that stuff. They’d take and dry them petals out, they’d mash ‘em down, mix them with hog lard back then, and they’d put it on their hands. And it’d make their hands smell good, and make their hands soft. And of course, they’d use it for rouge and lipstick, and different things like that. And of course, the second thing she taught us how to make was burn salve. It’s made out of plantain and slippery elm. But, my paw paw and them made moonshine (laughs) and, of course, they was always gettin’ burnt on the copper stills, the stills and stuff. And granny, of course, she’d run out there and douse ‘em with this mess! Of course it had kerosene in it too.

FF: Really?

RR: Yes, kerosene was a cure-all to my granny. She believed everything from a stump toe to kerosene and sugar would cure what ailed you. She was a firm believer in that. I remember being little and her taking kerosene and sugar and feedin’ it to all of us little ‘uns.

FF: For what?

RR: Spring clean out, she called it. You know, when you live up here in the mountains, you know, you’re drinkin’ out of streams and stuff you kinda get ringworms a little bit. Tend to get ‘em a little bit. Well she believed in cleaning you out whether you had ‘em or not. Kerosene on a stumped toe. The old house we lived in had just old granite rock steps in it. And, of course, running up and down, bare-toed, not payin’ attention where we’s going, we’d stump our toes and tear half the toenail up. And you could hear her coming from the back end of the cabin to the front end of the house, just a’ gettin’ it. She stood 6 foot 1 and weighed 265 pounds. She was a big ‘ol woman. You’d hear her comin’ through the house and we knowed as soon as she was comin’, she was gonna stop right up on that stoop and grab that kerosene can, she was comin’ after us so we’d run. We didn’t want that kerosene can no where near us.

FF: Did it burn?

RR: Oh Lord, yes! Like you, like somebody’d set you on fire! Yes, it burnt so bad, but, you know, it’d cure it. It never got an infection. Of course, us refusing to keep a band-aid or a piece of rag or anything on our feet, we was forever, you know, I mean it, but you know, we never got an infection or nothin’. But she taught us how to do that, and taught us, they call it faith healin’ now. Talk the fire out of burns and buy warts.

FF: Can you do that?

RR: I can talk the fire out of burns, but I’ve done passed the knowledge on and it has to go from male to female of non-related people.

FF: That’s what, my nana can do that.

RR: Yeah it has to, in other words I have to tell a male that’s not related to me by blood or marriage. It has to pass outside the family then he can actually pass it back to a female back inside of our family. And it’s it’s just done that way amongst mountain people through the years. That way it stays in the vicinity, it don’t leave it. So, and the same thing with buying warts.

FF: Can you buy warts?

RR: No I never did learn that particular trade uh Mr. White, the, one of the old timers that used to live up in these parts he uh, he could.

FF: My uncle could.

RR: Yeah he, he’d come up and tell you to give him a quarter. He’d take that quarter and he’d rub in on the wart and he’d go out in the yard and he’d walk out there for about 20 minutes. He’d go bury it, he’d tell you to go bury it. And it, it, a few days later it fall off. I mean, it works, and they call it faith healing now, I believe. We’re all what they call “granny witches.” You know, just healers.

FF: Say that again.

RR: Granny witches.

FF: Really?

RR: Mmm hmm. I ain’t never heard us called nothin’ else.

FF: Huh.

RR: I’ve heard root women, I’ve heard granny women, but up around here they were all called granny witches, and you’ll find that we’re called that all the way up through Kentucky and up through the Ozarks and everything. We are granny witches.

FF: I did not know that.

RR: Yep. There’s a, a blog that a little girl done. It really surprised me and you know like I done said I thought it was just somethin’ that was just indigenous to our area, and apparently that it’s not. Granny witches go all the way up through Kentucky. And the reason they were called that was because of the healin’ efforts. You know through you know a lot of people believed in superstition and magic back in the old days you know so that’s where the witch part come in. Healers, healin’ women, healers. And granny was a symbol of respect and wisdom.

Kenny Runion (Mountain City, GA)

FF: Do you think medicine’s good—like goin’ to the doctor—do you think that can help you?

KR: Yeah, it can help you, if you got an infection doctored.

FF: You think a doctor’s any good? Is he worth the money?

KR: Well sometimes he needs you, give you a shot.

FF: Do you think it’s better to use herbs and stuff from the woods or do you think it’s better to get medicine from a doctor?

KR: Well, I believe it would be better, if you’d use it, to get it out of this earth here. Well, you know, I know, I do know. I hope that Foxfire crowd, I guess who told you about it, she come down and I gave her a big lift on them herbs and things. I know everything here in the mountains, not a’braggin’. Poke root, ginsang—you’ins know that, don’t you?

FF: Yeah.

KR: ‘Simmon bark.

FF: Where’d you learn all that about herbs, Kenny?

KR: There used to be an ol’ Indian doctor come and stay with us a long time. And if ever I hear anything, I’ve got it. I’ll remember it. Now there’s the ‘simmon bark, makes the best poultice for a risin’ in your life. It’s ‘simmon bark. And that poke root—I know you know what it is. It’s as poison as a string. You dig up the bottom part of it, you know, the root of it, and roast that stuff like a sweet tater. Lay you down somethin’ like a clean cloth. Just rub her off like that on that. Put it to the bottom of your foot, and if you got a risin’ anywhere, it’ll draw it out. I don’t care how black your foot is, when you pull it off, it’s as white as cotton. You can feel it given that. Drawing.

Patricia Kyritsi Howell (Clayton, GA)

FF: Okay, What sort of education, or certification that you need to be an herbalist?

PH: Well that’s a very controversial topic.

FF: Really?

PH: Yes, Because until very, very recently—well, first of all, the U.S is kind of unique because we don’t have any kind of recognition for the practice of herbalism on the federal or state level, that means that anybody can call themselves an herbalist even if they don’t know anything—you know you could call yourself an herbalist it doesn’t have a legal definition. We are the only industrialized country in the world that doesn’t recognize plant medicine as a legitimate form of medicine.Until really recently, now there’s a couple universities offering a Masters in Herbal Sciences. So this group that’s coming through in a few minutes are students at Bastyr University which is outside of Seattle and it’s a naturopathic college so they study basically to be a naturopathic doctor which has very similar training to what a regular doctor would do, but instead of using pharmaceuticals they use supplements and herbs.

FF: I see.

PH: Okay, are you getting the picture? So, in the United States around World War I, 1912-1915—around that range of time, the majority of the amount of doctors who practiced in the United States were naturopaths. What happened at that time was that there was a, well first of all during World War I, a lot of nerve gases and chemical weapons were developed particularly by the DuPont corporation. And as a result of all that, they developed a lot of medicines out of that. Drugs came out of that. So when World War I was over, they had this whole industry that was based on manufacturing chemical weapons for warfare. And as a sideline, they developed some drugs. We live in a place in this country where this whole tradition of using plant medicines and foods as therapies was very consciously denigrated. One of the things that makes the Appalachian mountains so unique, was that because of the isolation of the mountains and the people living here, that tradition was never wiped out. It stayed intact, a lot to do with the fact that not a lot of people had access to any other medicine and they didn’t have a lot of money. So they kept using plant medicines. Most of the plants that people use as herbalists are plants that are native to the Southern Appalachians. Even in other parts of the world. Do when I was in Greece one time, I went into an herb shop and the herbs that they were selling—two-thirds of them are things that grow wild here. So those are likethe plants that are—that’s what so amazing about this area. It’s referred to as the ‘Apothecary of North America.’

FF: Yeah, you were mentioning something about that when I first got to meet you.

PH: Yeah, so we have this wealth here that we need to also protect through conservation. So that’s another alliance that I hope we’ll be able to make within the next year with some of the medicinal plant conservation groups that are operating in the country, to make sure that everything we teach people about plants here also incorporates information about what’s endangered, what’s at risk, and things like that. Because we don’t just want to say here’s this plant and it does all these amazing things and let people go out and over harvest it.

FF: Oh, yeah, I hadn’t really thought about that.

PH: Yep. So have any of you seen lady slipper? Pink lady slipper or yellow lady slipper?, well that herb, the roots of that plant, um if you make a tea out of it it’s a wonderful sleep aid. It’s like you drink a tea of that and all of a sudden you just have this wonderful drowsy feeling and you just want to go to sleep and you fall asleep and you have a great sleep and you have a good dream it’s really wonderful. And so when the Europeans came here and they learned about that medicine, because it is such an obvious plant you can’t mistake it for anything else, it was being over harvested for hundreds of years and exported to Europe as medicine at the time. And if you dig up one of those plants, the roots of it probably weigh one-sixteenth of an ounce, each plant. So they were exporting like thirty tons out of Savannah every year. So that plant is now protected throughout its native habitat, specifically because it is such a good medicine that it was over harvested. So we want to make sure that it doesn’t happen to these other plants.

FF: Are there any other plants now that this is happening to?

PH: Yeah, a lot. Like Black Cohosh is one, that’s a very common woodland plant here. Bloodroot, of course Ginseng is very protected, technically. Blue Cohosh is another plant—all of which grow here on this mountain.