The Foxfire Textiles:

Within the Foxfire collections are over forty unique textile artifacts. The bulk of these are either quilts or handwoven coverlets. Nearly every artifact was donated by a magazine contact or a relative of that contact. This online exhibit features many of these textiles and delves a little deeper into the stories behind them.

Quilts:

Quilts have been used around the world for hundreds of years for warmth and cover. Quilting, by formal definition, is the stitching together of layers, creating a stronger and warmer fabric than a single layer of cloth. The decorative work often associated with quilting, the intricate block patterns like log cabin, are technically the patchwork. What classifies these as quilts are the stitches securing the layers. In this category, though, we’ve included tied quilts, “summer” quilts without layers, and quilt tops, as all were done in the spirit of quilting. Quilts are often passed through families as heirlooms, with the more decorative and design-focused quilts surviving the longest. Surviving functional quilts, ones that were used and reused for warmth, are rare in both museum and private collections. Worn thin or ragged, these quilts often are seen as less valuable. However, Foxfire is fortunate enough to have a few of these preserved textiles within our collection. These examples provide an intriguing contrast to the more formal quilts, with longer, hasty stitches and clothing scraps – used to produce a warm quilt in a hurry or with few resources. The quilts selected for this exhibit illustrate the different types and reasons for quilting, and provide a comprehensive overview of the Foxfire collections.

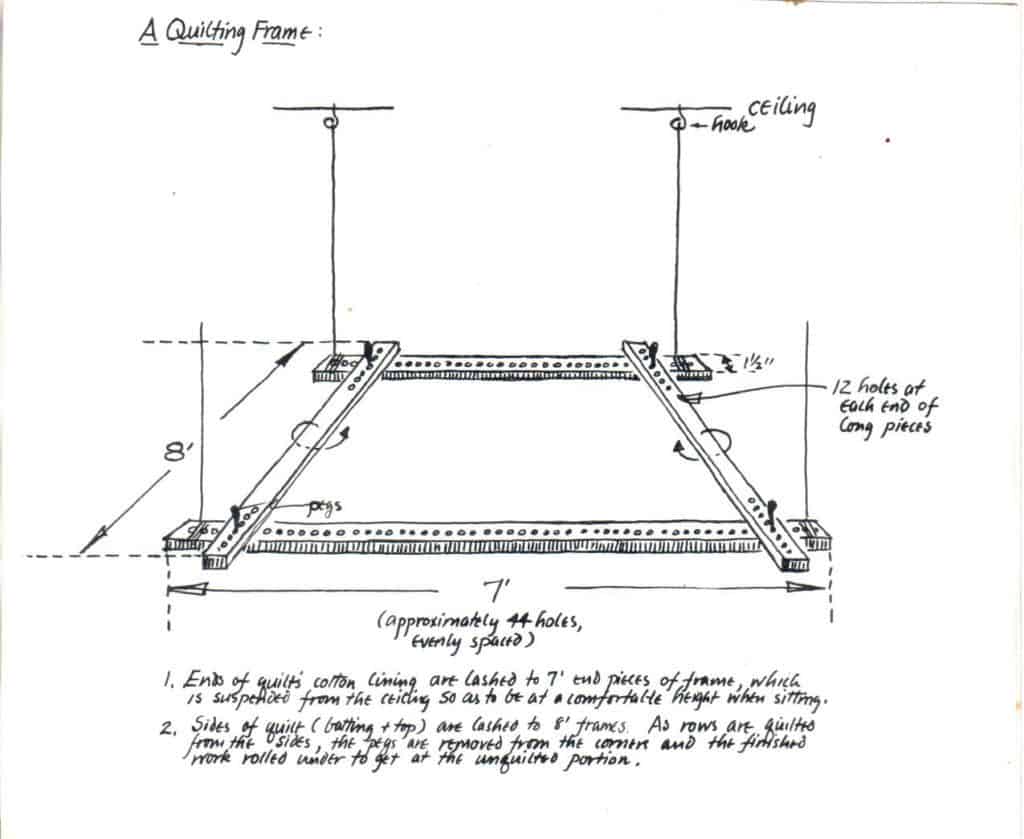

Though created by an individual, it was fairly common for a community of women to come together and pitch in during the quilting process. Known as quiltings, or bees, these were informal gatherings hosted by the woman who owned the quilt. This was also done for community-made quilts, like friendship quilts or the anniversary quilts gifted to Foxfire. Quilts were wrapped around the edges of a quilting frame, which would be suspended from the ceiling, then each woman would take a section and quilt in the desired pattern.

Diagram of a quilting frame.

Quiltings continue to this day and are valued for the socialization, but also for the meaningful use of leisure time. Women, and men, are producing something that they can take great pride in. No matter the quilt, “fancy or plain, however, the fact remains that quilts seem to us symbolic of some of our finer human qualities” (from “A Quilt is Something Human, Foxfire, vol. 3 no. 3).

Weaving

Weaving has a deep history in the mountains. Until the early twentieth century, manufactured cloth was largely unavailable, or unaffordable, to mountain families. Clothing instead was made from cloth spun and woven from family sheep, or perhaps from flax grown locally. Although household weaving was typically carried out by women, the process of yarn preparation involved both boys and girls. Children would learn to card, or comb, wool at around four years of age and by age six they were spinning the wool into yarn.

Mrs. Dean Beasley demonstrates weaving.

Most households used either a countermarch loom, where the beater is suspended from above the warp, and rocker-beater looms, where the beater is supported by two rocker-style feet. The latter loom model is believed to be original to the Southern Appalachian region. Both of these loom styles are on display at the Foxfire Museum.

Many women interviewed by Foxfire students were still actively weaving in the 1970s and 1980s. Throughout the region, the craft saw a revival during the Great Depression, when the WPA established schools to teach folk arts, but many women in Rabun and Macon Counties learned from their mothers or mothers-in-law either as they were growing up or shortly after they were married. The women they learned from passed on their passion for the craft.

Gertrude Keener on pattern weaving:

“When you watch your pattern grow, t’me it’s like life—more like living. It’s more like building character than anything else I can describe it with. It’s like teachin’ a child from the beginning to grow. As your pattern grows or as your cloth grows, it’s just like a child growin’ up. You weave your life into somethin’ beautiful. That’s the way I see it.”